Childhood Treasures

When the Germans gave us twenty-four hours to clear out of our home and to take only that which we could carry, my toys were not among the necessities Mother and Dědeček packed. Thus, I landed on the Tůma farm a four-year-old without his trucks, tin soldiers, and miniature sailboats. However, my ever-thoughtful mother made certain that I would have something that would help me through months of boredom, frustration, fear, and loneliness. She packed three of my favorite books. During the next four years of survival and loss of a normal childhood, these books would be my closest and dearest companions. I would read them over and over until their words would be transported from their frayed pages into my memory.

There was Čítanka, roughly translated as “Reader”. The tagline read: “Selected and Arranged for Czech Children.” It began with the lyrics of the Czechoslovak national anthem and a patriotic essay titled “I am a Czech.” Its three hundred pages were filled with stories and poems selected such that they would simultaneously entertain and educate the young reader. I loved the book even more after Mother warned me to hide it each time I finished reading because it was outlawed, due to its patriotic tone, by our German occupiers. And I took to heart the final passage, one that would be my guiding light for a lifetime: “A book is your best friend. It will not disappoint, abandon or deceive you. A book is the best companion because the best people put into it their best, that which resided in their souls.” To which I reply—now in my ninetieth decade on this planet: “Amen.”

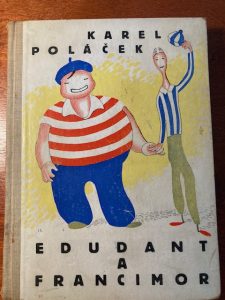

Much less serious was Edudant a Francimor, written in 1933 by Czech storyteller, Karel Poláček. The famous sorceress Halabába had two sons, Edudant and Francimor. One day, she sent the boys to town to get her bicycle, one on which she performed her magic tricks, repaired. But once in town, the boys encountered the school inspector who confronted them about failing to attend school. Once forced to start going to class, the sons stole their mother’s magic broom, aboard which the entire class escaped from school. And so continued the adventures until Edudant pretended to be a physician and using magic, cured the king of an incurable disease. As a reward, the king offered Edudant and Francimor his two daughters. They refused to marry and returned home only to find out that they had been expelled from school. This made the brothers very happy and they spent the rest of their lives as sorcerers. The book was illustrated by Josef Čapek, a famous Czech artist and brother of the even more famous writer, Karel Čapek. Josef invented the word “robot,” which was introduced to the world in his brother’s play, R.U.R. Sadly, Josef perished in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. One of his paintings hangs on my wall.

Finally, there was the book that fed my dream to become a great explorer once my father would free our country of the hated Germans. It was Robinson Crusoe, written in 1719 by Daniel Defoe. Robinson’s ship was destroyed by a storm near the coast of Venezuela. Only he, the captain’s dog, and two cats survived the shipwreck and ended up on a small island. There, he encountered cannibals and mutineers. With weapons and tools he rescued from the sinking ship, he managed to build a habitat and to protect himself from enemies and wild animals. He helped to save an escaping prisoner, who became his servant. He named him Friday after the day of his rescue. Eventually, both Robinson and Friday were rescued by a merchant ship, and their adventures continued after their return to England.

While I was captivated by the adventures of Robinson Crusoe, I found something troubling about my hero. The ship from which he was thrown into the sea had been part of an expedition to purchase slaves in Africa. At first, my four- or five-year-old self skipped over this fact without giving it much thought. It was only a couple of years later, when Mother presented me with a copy of the Czech translation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that I began to understand that there were horrible people in this world who owned other people. In the war’s last year, the concept of slavery would become personal—when Mother was carted off to a slave labor camp. Now, I understood and detested slaveholders everywhere—Europeans and Americans of the past, and Germans of the present.