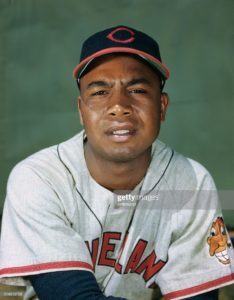

Larry Doby

Continuing to post short vignettes from my upcoming “coming-to-America” memoir, Cowboy from Prague, here is a story about a man who became my hero:

Continuing to post short vignettes from my upcoming “coming-to-America” memoir, Cowboy from Prague, here is a story about a man who became my hero:

As a boy in post-war Europe, I had been a good athlete. I excelled in soccer, hockey, skiing, and tennis. No doubt, I inherited my father’s genes. He was not only an outstanding competitive volleyball and table tennis player, but he and a friend were co-holders of the European distance record in one-man kayaks. We were a very sports-oriented family, but I had never seen—nor even heard of—the most popular sports on this side of the Atlantic: baseball, American football, and basketball.

Our Franklin Village apartment was directly across the street from a concrete court where, each afternoon and evening, a group of boys played basketball. After a couple of weeks, I got up the courage to approach and stand on the sidelines. There, I learned a bit about the game from observation. Finally, some of the older boys began speaking to me and even invited me to play a few minutes at a time.

After several weeks of being the worst player on the court, I began to understand the game and, by the end of summer, I was good enough not to be the last player chosen by the captains when they selected their teams.

Beyond the basketball court, in an open area today occupied by Morristown Memorial Hospital, was a baseball field. One day, I spotted two boys playing catch. Each was wearing a leather glove, one on his left hand and the other on his right. Emboldened by my success at basketball, I walked up and introduced myself to the guys and asked if I could join in. The right-hander, the one with the left-handed glove, told me his name was Jim Gerber. He loaned me his glove. I tossed the ball back and forth with the lefty: tall, bespectacled Pete Brown.

I convinced my father that I had to have my own baseball glove. He accompanied me to Ken Mills’ sporting goods store, where we purchased a light brown number. Pete and Jim taught me how to break it in, and the three of us met every afternoon for a game of catch.

One Saturday afternoon, Jim and Pete invited me to go with them to see a baseball movie about a guy from a nearby town at the Park Theater in Morristown. The Larry Doby Story depicted the life of a boy who had been a three-sport star at Eastside High School in Paterson, New Jersey. He signed a professional baseball contract at the age of seventeen and, almost immediately, became an all-star for the Newark Eagles. However, both his education and athletic career were interrupted by service in the US Navy during World War II. By war’s end, young Larry knew that baseball was his best sport. He had played against major-league stars as a seaman, and he had no trouble hitting the game’s best pitchers. Without a doubt, he could play at the highest level of the game.

There was only one problem. It was 1945 and major-league baseball was a lily-white game. Larry Doby was black. His only future was in the Negro Leagues, a traveling roadshow of talented, underappreciated, and underpaid athletes. He returned to the Newark Eagles in 1946 and led them to the league championship.

Then came 1947, the year Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers changed America’s pastime forever by making Jackie Robinson, a brilliant athlete out of UCLA, the first African-American to wear a major-league uniform. Less than three months later, Larry Doby became the centerfielder of the Cleveland Indians and the first black player in the history of the American League.

My English was still limited and I failed to comprehend some of the movie’s dialog and nuances. But it mattered little. The story of Larry Doby—his successes on fields and courts, his patriotism and dedication despite the humiliation and rejection he suffered—captured me. As a “hidden child” of World War II who had been victimized by the Nazis and now was a refugee in a strange land, I identified with his struggles. By the time Pete, Jim, and I walked out into the afternoon sunshine, I had a new hero, one who would influence my life for years to come. I would wear Larry’s number 14 on the uniforms of all sports I played. When it was unavailable to me as a college basketball player, I wore its reverse: 41. Many years later, while our company was computerizing major league baseball, I finally met Hall of Famer, Larry Doby. He told me how touched he was by the effect he had on an immigrant boy, now the CEO of a software firm.

“I’m really proud to meet you, Charlie, and even prouder that I was able to inspire you,” he said, and I felt as if I had ascended to heaven.